After 25 years, writer Katie Arnold returned to Long Caye, a slice of paradise that the adventure travel boom forgot.

It’s a bright, windy December day, and we’re on a boat barreling east from Belize City. For nearly three hours, the Caribbean has been choppy and rough, until the water abruptly goes still. The sudden calm can only mean we’re inside the reef. We’re almost there.

I poke my head through a porthole in the ceiling. Ahead of us on the blue horizon, a small island is growing bigger and more distinct. Longer than it is wide, it appears to consist of palm trees, a narrow crescent of yellow-sand beach, and, at the north end, a cluster of wooden, thatch-roofed cabanas. A small dock on the lee side awaits. Figures emerge, arms raised in greeting.

Belowdecks, someone’s kids are shrieking like lunatics.

I blink, letting my eyes adjust to what I’m seeing, waiting for my mind to catch up. Am I here or there? Is it then or now? What I’m seeing makes complete sense, and also it doesn’t. I’ve gone across the sea and back in time.

My first visit to Long Caye was in 1997. I was 25, with a low-paying job as an editor for this magazine. I had a boyfriend, a rental casita, and almost no responsibilities outside of work. It was not my plan to publicize Long Caye. That happened later, after my boyfriend and I had lived like quasi-castaways for five days on this little wisp of dry land in the middle of Glover’s Reef Atoll. After we knew what we’d found, and before it would feel too fraught to share it.

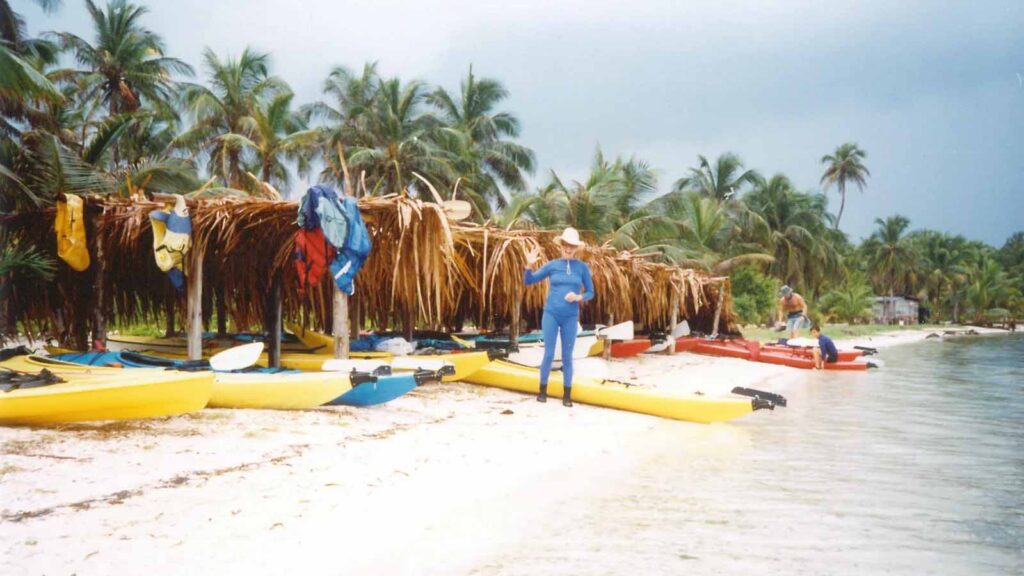

At the time, Long Caye epitomized the emerging trend of ecotourism: a private islet 60 miles off the coast of Belize, on the edge of the second-longest barrier reef in the world. Less than half a mile long, it had no electricity, no telephones, no flush toilets. Wi-Fi hadn’t been invented yet. Glamping wasn’t a word; it was a typo. The place was simple—only a handful of cabanas with shutters that opened to the windward breeze, a sizable fleet of sea kayaks, and hundreds of pristine patch reefs for snorkeling and free-diving close to shore. Cully Erdman, an affable, sunburnt desert rat who owned a kayak school called Slickrock in Moab, Utah, had taken out a lease on Long Caye a year earlier, in 1996. He drove a vanload of kayaks down from Utah and applied the same name here. An island outpost was born.

How we found Slickrock is impossible to remember. The internet existed, but back then we still made phone calls. We talked to friends who knew of such places in order to learn about them. We… read guidebooks? We prided ourselves on digging up true finds—little-known, out-of-the-way destinations with character. This was before Instagram, a time when, by today’s standards, many of these places were hardly known. The most you could do was let your buddies back home in on the secret, order doubles of your snapshots, and hang them on your fridge.

The shrieking children belowdecks belong to me.

Reverie broken. I am not 25 but twice that. I’m married, with two teenage daughters and a husband. I have a husband! He is darling, and the reason we’re here. Months earlier he announced a wish to celebrate his 50th birthday by going bonefishing over the Christmas holidays. A small worm in my brain unearthed a distant image—beaches, hammocks strung on porches, sandy flats along the edge of mangroves where bonefish might lurk. Slickrock.

Improbably, I invoked a method of communication popular in 1997: I dialed a phone number. Improbably, in Belize, a woman named Marcy Norales picked up.

There ought to be a word for the peculiar mix of anticipation and dread you feel upon returning to a place after a long time away, simultaneously excited to be back and fearful to find it unrecognizable. The word would be German, of course, expansive enough to hold two contradictory emotions at once, the way Slickrock’s current owner, Phil Dowsett, appears to when we meet him, his pale face both jubilant and a tiny bit crestfallen, like he’s worried, too.

We bustle onto the dock, along with four friends and their three kids. Together we’re 15 in all, counting two younger couples—one of which, a pair from Alaska, are taking their honeymoon five years late. At peak occupancy, Slickrock can sleep 30, but during the week before Christmas, when we arrive, it’s conspicuously quiet.

Wi-Fi hadn’t been invented yet. Glamping wasn’t a word; it was a typo. The place was simple—a handful of cabanas with shutters that opened to the windward breeze.

“Hold on!” Phil cries, dashing away, returning moments later holding a laminated cover of Outside, faded and curling at the edges. A photo of Slickrock was used to illustrate a cover package on bucket-list goals—including one called “Get Marooned”—and the cover models were slim and young, posing with surfboards in front of a bungalow. After the issue came out—in December 1998—Cully wrote to tell me that it had helped put Slickrock on the adventure map. I was mostly glad, a little bit conflicted. It would be a decade before social media radically transformed the landscape of travel, but even back then Slickrock was too good a secret to keep.

Now, looking into the expectant eyes of my family and friends, I can’t help but wonder: What if I’ve dragged us here based on faulty memories, a broken promise of an off-the-grid idyll? How can Slickrock have survived the age of the internet, digital tourism, over-tourism, Instagram? What if it’s a derelict relic from another era?

Somehow, all the possibilities turn out to be true.

When Slickrock Belize opened on Long Caye in 1996, Cully envisioned a tropical multisport paradise with surf kayaking, sea kayaking, windsurfing, and snorkeling, plus Belizean guides who taught you the skills you needed for a week of playing hard in the water. It was like a river trip on an island: Meals were served family-style in a sandy-floored dining room, and the emphasis was on group instruction. If you didn’t know the other guests when you arrived, you were friends by the time you left. Slickrock wasn’t a resort in the fruity-rum-drinks sense—it didn’t have a bar then and still doesn’t—nor in the shoddy-gear-that-few-people-use sense. It was a base camp that took adventure seriously.

After 27 years, it still does. Our days fall into a pleasing rhythm. I wake at first light to watch the sun from the porch of our private palapa. Breakfast is at 7:30; the two guided activities of the day, listed on a whiteboard, follow at nine and two. Lunch is at noon, and in between snorkeling or kayak sessions there’s time for hammock lounging, reading, or napping. Sunset drinks and snacks are at 5:30 on the beach—or after paddleboarding to the south end of the island. Dinner is served promptly at seven, followed by a guide talk on marine life, the history of Belize, or Slickrock itself. Afterward, if we can muster the energy, we play a few rounds of beach Frisbee before bed, beneath a moonless sky, the stars a billionfold and gleaming.

At 25, I was vaguely irked by the group activities: I didn’t want to hang around with a bunch of strangers and their kids. Now, though, I find it relaxing, even liberating. I don’t need to make or execute any plans for myself, my husband, or the children. Simplicity is the ultimate luxury at Slickrock, and the only decision of consequence each day is whether we want to snorkel in the morning and paddle in the afternoon or vice versa.

The kids make their own rules, choosing from a seemingly secret array of activities that don’t appear on the whiteboard. They swim with nurse sharks in the bay, learn to scuba dive, and construct elaborate obstacle courses for resident crabs. At four each afternoon, they husk coconuts with our three guides and drink the water straight from the shell. For hours, they kayak-surf the reef break on the north end, small bodies in bright boats and helmets, bobbing amid the breaking waves, dropping over the lip and riding the curl all the way in.

When we’re not snorkeling among parrotfish, octopus, and honeycomb trunkfish, or paddling the rolling swells around the east side of the island, I’m making a list in my head: things that are the same, things that are different. The former far outweigh the latter. The island was hit by a hurricane several years ago, and the kitchen, a simple clapboard structure painted bright blue, had to be rebuilt a few hundred feet away. A small, off-the-grid dive operation now occupies the island’s south end, just beyond the dock. By far, though, the biggest upgrade is offshore: a cell tower five miles away on South Caye that on most days sends a signal that’s strong enough, sadly, to let the outside world in.

REad MOre : All the Fish We Cannot See

Other than that, the island seems utterly unchanged. Has anyone cleaned the toilet tanks since 1997? Debatable. And yet Slickrock’s surreal time warp is wildly charming. The cabanas catch the breeze, unlimited Belikin beers are free for the taking. Neri Chi, a guide who was there back in 1997, is here for our trip, still teaching windsurfing. The coral reefs, which see a fraction of the snorkelers that reefs closer to the mainland do, are still healthy and alive. The bonefish are suitably elusive but biting.

The main thing that’s missing: guests.

When I came to Slickrock in 1997, Cully was a gregarious visionary with infectious energy for the island and the guiding life. But in 2018, in the midst of a cancer scare, he sold it to Phil, a soft-spoken, instantly sympathetic character in his mid-thirties whose first words upon meeting us were: “I’m sorry. I mumble too much.” If there’s an anti-Cully, it’s Phil—and yet there’s something strangely endearing about him. How did he end up on this spit of sand in the far-western Caribbean, and how will he ever make a go of it?

One night after dinner we get the full story, delivered by Phil in his signature murmur. He dropped out of high school in England at 16. Then, at 19, he opened a mobile zoo out of his van. Later, he worked for a leopard sanctuary featured on the UK version of Animal Planet, and was bitten by a python. In 2012, when he was on the verge of buying Slickrock, he got hit by a car and broke his back; the medical bills nearly sank him. He lost the investors he’d lined up and had to start from scratch, pitching a modest Slickrock revamp to the Belize ministry of economics, only to run into delays and red tape. It would take him another six years to scrounge up enough to buy Long Caye, in 2018. Then the pandemic hit. Visitors have returned to Belize, but as Phil tells us, business has been slow to recover at Slickrock.

This is one of the most rousing stories of tenacity I’ve ever heard, but when I turn to the kids to make sure they’re listening, their chins have collapsed into their hands. Around the room spirits are sagging, heads bobbing, the audience wearied equally by Phil’s chronic misfortunes and the late hour. Night falls hard in the tropics. Later I drift off to the rush of waves and wind, feeling simultaneously better about Phil and a tiny bit worse.

My women friends and I are going hard while the husbands fly-fish and the kids amuse themselves by filming GoPro footy of sharks, trying windsurfing and scuba diving, and kayak-surfing so rabidly that they smash their palms on sea urchins and have to get our guide Mario Chub to extract the spines with tweezers. We’re paddling out to the reefs, tossing our little anchors overboard, snorkeling amid purple sea fans and hawksbill turtles—and, at the same time, scheming up ways to help Phil bring Slickrock into modern times.

Candles, we decide. We’re lying on our backs on the surfing dock. The children are still alive; we can tell by the peals of laughter that rise occasionally over the crash of waves. If there were a few candles placed artfully here and there, in the bathhouses, you could call this glamping. Toss in a few bright textiles, white sheets on the beds, and some groovy solar-powered lanterns, and Slickrock would be sold out all season.